What are CAT tools

If you deal with literary and creative translation only, you have probably never used any special translation-related software other than dictionaries (and a word processor), but you may have heard of “Computer Assisted Translation” tools or CATs for short. These were developed with technical translation in mind, and their main premise is to “never translate the same sentence twice”, which makes a lot of sense in the world of repetitive instruction manuals, but can this be useful in literary translation? Let’s see, but please note that this text does not touch the subject of machine translation (MT).

Let me start with a short introduction: I started translating literature in 2000, while still working on my (failed) Ph.D. in chemistry, “retyping” paper books into a text editor. Several ergonomic improvements later, it was finally electronic text in two windows on a single screen. And somewhere along the line, I started translating “technical” texts as well (medicine and chemistry), where the use of CAT software was a requirement. And after I got used to the software, I started using it for literary translation too at some point. And never looked back.

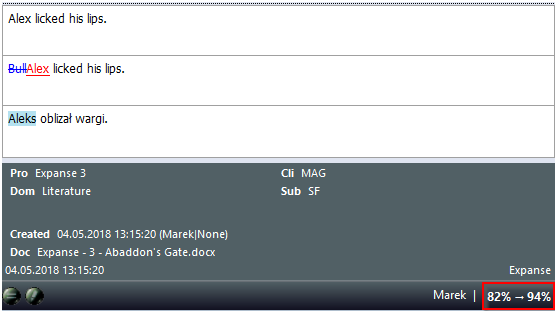

So what’s the deal with the CAT tools? The main idea behind them is that the text for translation is “segmented” into sentences, and once you translate a sentence (segment), both source and target are stored in a database called a “translation memory” (or “TM”), which you can use in the future translations and share with others. When you encounter identical segments in the future, the software will insert the prior text into your current translation, so you don’t have to waste time on something you – or someone else, if you received a translation memory along with the files for translation – already did, while ensuring consistency, which is very important in technical communication. If you encounter a sentence similar to something you already translated (a so-called “fuzzy match”), the software will also show you the previous translation with differences between the current and previous segment texts highlighted, again helping you work faster and in a more consistent way.

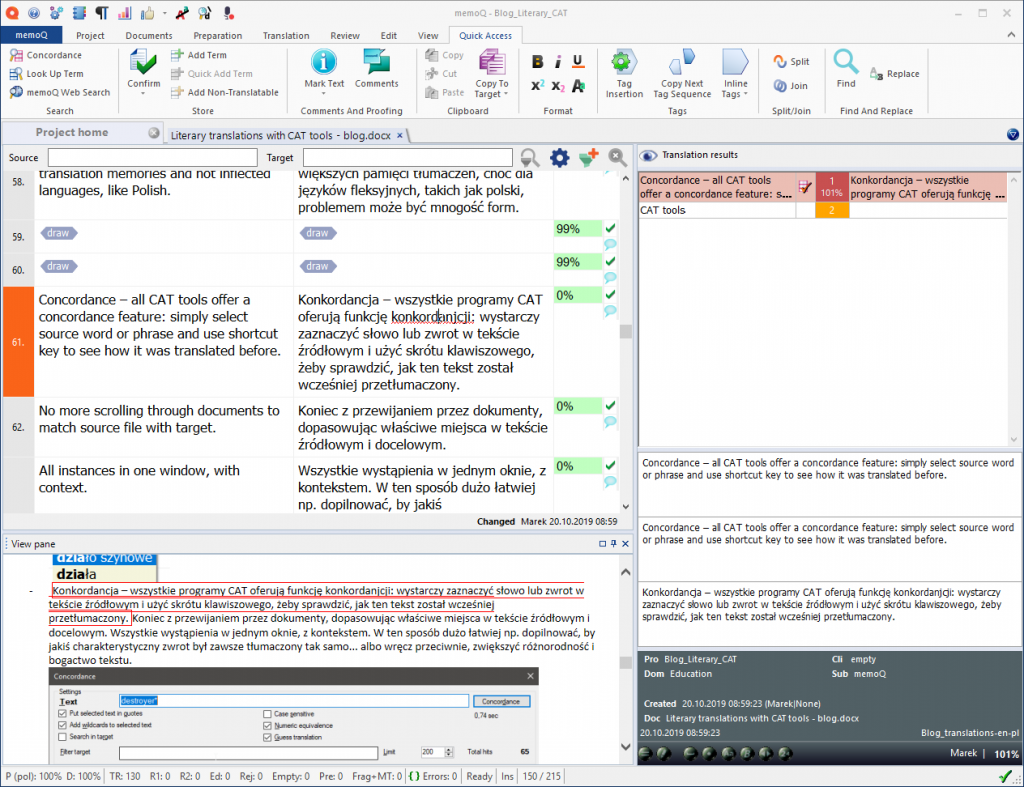

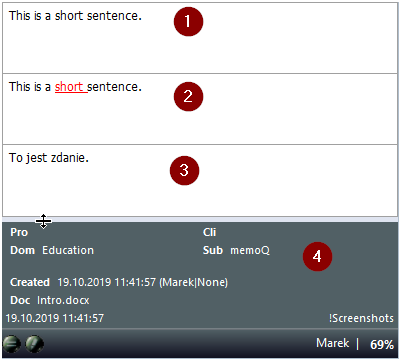

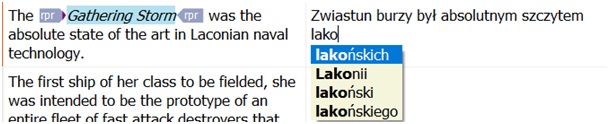

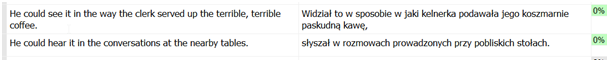

Translation memory match in memoQ: (1) Current sentence for translation, (2) Similar sentence found in translation memory, highlighting differences between current text and TM match (3) Translation of the segment found in TM, (4) Information on TM match: who translated/edited it, when, what was the document name, similarity score (match percentage) etc.

Of course, that’s not necessary something we want in a literary translation, but it’s sometimes useful, and the CAT tools offer way more than just help with consistency, definitely helping me work in a more comfortable, efficient way. Let me tell you how.

Benefits

I never actually did the translation in Word thing: I used a Linux text editor, but the idea was the same: open the source text in an editor window, open a second window to the right/left/above/below, make sure the windows are right size and in the right places, and then you can translate. Also, once in a while you need to switch to the source text window to change the scroll. And if you take a longer break for any reason or close the source text window, you need to find where in the source text you now are. It doesn’t take long, but this adds up in the course of a work day.

When you work with a CAT tool, some preparation is required at the beginning in most cases, as most tools employ the concept of a “project”: you need to create a project with a name, define a language pair and create a new translation memory and term base or mark existing ones for use, and then import the source file. For something you’ll do once in several months it’s really not a big deal. Once you have done this, you can run an analysis in which the software will tell you how many segments/words/characters source file has and if there are any repetitions – identical segments written more than once in the text. For literary texts, in most cases this will be things like “Chapter:” and for an English source text also “he/she said” and the like. Running an analysis is a great way to track your progress: while the software will display progress information in real time, I like being able to record this information, so I always run analysis at the end of my working day to be able to track and compare daily progress. But it’s optional, and the number of characters/words should be the same as reported by a word processor.

Let’s start the translation. Once the text is imported, you can open it for translation. Depending on the actual software used, various levels of formatting will be shown – some programs, like Trados Studio, replicate font color, size and typeface from Microsoft Word documents while others, like memoQ, show only most basic formatting (bold, italic, underline), using single, customizable font face for all text. I actually prefer this approach, since it’s easier to focus on content.

Let’s list the actual benefits of working with a CAT

- Focus/ergonomics – Regardless of the fonts, in case of most CAT tools the source text will be displayed as segments: each sentence separately, and you are supposed to type in the translation – depending on software or settings – to the right of source or below source text. This has three benefits: it helps you focus on a single sentence and makes it easy to find the current text to work on – it’s usually in the middle of the screen, highlighted in some way. It’s also really hard to forget to translate some part of the text: you’ll get a warning if you’ll try to export a translation that’s not completed.

- Formatting – You will see more or less “clean” text (the amount of formatting depends on the software and your preferences). If the paragraphs are formatted in some complex way, you don’t have to worry about that, software will use that formatting when you export finished translation. You can just focus on the translation, applying simple stuff like bold or italics along the way or using special tags for more complex formatting.

Original source text formatting is usually displayed as a live preview in the CAT tool interface (but not in all such programs), and the preview is updated as the translation progresses.

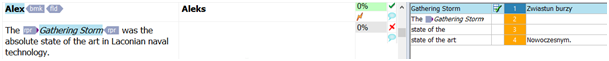

- Term bases – You can use term base (glossary) features to speed up your work and make it more consistent. Do you need to translate some place name? Add the source term and its translation to the term base (TB). If the name shows up in a source segment, it will be highlighted, and the translation will be shown somewhere in the CAT tool’s user interface. You can then insert the translation quickly by double-clicking, using a shortcut key or just by starting to type it and using the predictive typing suggestion. Do you have a long, complex place/person/company/product name? Add it to a TB to facilitate quick typing or insertion. Are you translating from English to some inflected language and there’s some character in your novel whose gender you can’t remember? Add the name to TB with note on gender. You can type it faster and see the gender info quickly.

- Faster typing – Term base hits can be inserted very quickly, but this also works for short segments. Plus in some programs like memoQ or Trados Studio you can generate special predictive typing dictionaries that will suggest words or even multi-word phrases based on source segment content. This works best if you have large translation memories and languages which are not inflected.

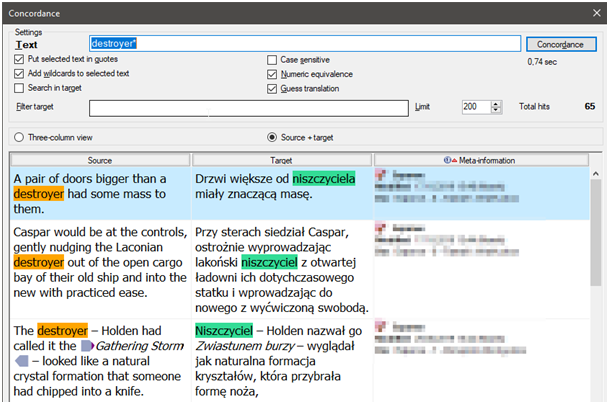

- Concordance – All CAT tools offer a concordance feature: simply select source word or phrase and use the corresponding keyboard shortcut or function button to look up how it was translated before. No more scrolling through documents to match source file with target. All instances in which the expression occurs are shown in one window, with context. This makes it much easier to ensure consistent translation of some particular phrase used by one of the characters, or just the opposite – ensure diverse translations if preferred.

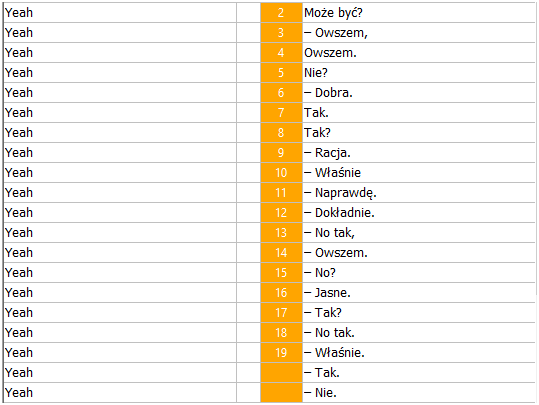

- Auto-concordance – It gets even better: short, repeated segments (like “he said”) and their translations can be shown automatically. You can use this feature to ensure consistency or as a sort of thesaurus for increasing diversity, which is often needed in a literary context.

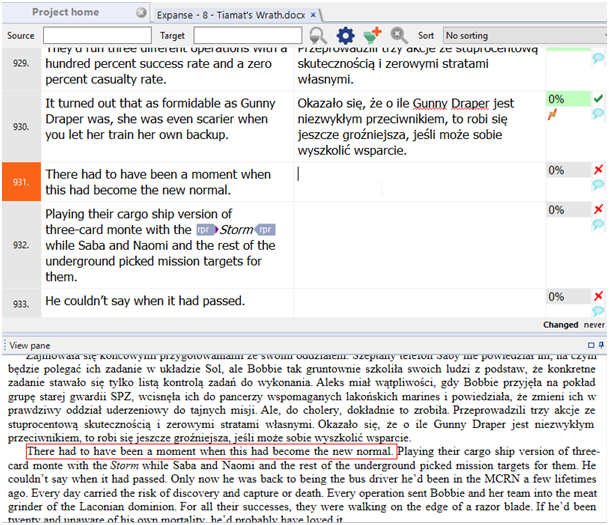

- Quotations – Does your author repeat statements made earlier? How well do you recall these? You don’t have to look for the quote; the CAT tool will show you previous the translation automatically. And even show the differences if the author changed something (deliberately or accidentally).

- Comments – Do you use comments to note something for later? No problem! You can use the commenting feature in your CAT tool and perhaps assign one of various comment categories (e.g. information, warning, etc.) for different purposes. Later you can filter to find the segments with comments quickly and even export those comments (all of them or just a selected category) to the target document.

- No sentence is lost – Once you confirm a segment (usually with Ctrl-Enter), it gets marked as confirmed in a translation editor, but it’s also stored in a translation memory (database). Some programs save the file at the same time (in others this happens at pre-defined time intervals). Even if your computer crashes or there’s a power outage, the translation is safe – you can always restore it from the translation memory. This provides another level of safety/backup for your work.

- Progress tracking / improved productivity – A CAT tool will show your progress based on the number of segments, words or characters. I already mentioned the analysis feature and real time progress information. But working with segments has an additional benefit: you can use them for a variant of the Pomodoro technique, where instead of time, you focus only on your translation for a given number of segments. For me in literary texts it’s usually 50 – when I start working, I ignore emails and other distractions until I’ll translate 50 segments. Then I take shorter or longer break (for Facebook, preparing tea or loading the washing machine) and start another batch. The number can be different depending on the complexity of your source text, but this technique allowed me to improve my productivity considerably. Of course, you don’t have to use a CAT tool for this; you can do this based on pages instead of segments, but I find it easier with segment numbers.

- Filtering for words/phrases – You already know that it’s easy to check how something was translated before, but what if you changed your mind and you want to use a different translation? Use Find and replace… or filter the text based on a source or target expression and edit the selected segments containing the words you need in context. Please note this feature is not available in all CAT tools, only those which use an editor with a “table” interface.

- Built-in/optional web search tools – You won’t find this in every tool, but the good ones have it. Do you need to run a Google/Bing search or use some web dictionary? Once you configure built-in/optional web search feature, you can just select a word or phrase and use shortcut key to look up that text on multiple web sites at the same time.

- Automated fuzzy matches correction – This doesn’t happen very often in literary text and it’s may not be something you rely on, but sometimes a fuzzy match (sentence stored in TM similar to your current one) can be “fixed” automatically to create a correct translation. And it may even be something worth keeping without rephrasing.

There are also other useful features, like: being able to generate a Microsoft Word file with source and target texts in a table for quick verification in the word processor’s environment; auto-correction lists; the ability to use monolingual reference files; quality assurance functions; and much more.

Limitations

So is it all roses? As with any software, there are some limitations.

- Sentence-based translation – As mentioned before, with CAT tools we are working with segments, which are mostly sentences. But in literary/creative translation we need to consider the larger context, usually a whole paragraph or more, and the stylistic impact on a reader. Context and style are, of course, important in technical translation but are often weighted differently.. Breaking text up into sentence-level chunks makes it easier to focus on the current segment, but at the same time a bit harder to think about whole paragraph. But it’s not like the rest of the text is hidden – just the opposite, current segment is highlighted element with previous and next segments plainly visible, so it’s just a matter of adjusting how you look at things. You can also easily change the segmentation to paragraph-based, but this may negate some of CAT benefits (e.g. it’s easier to miss a sentence). Quite often you will also have to change sentence length – joining two or more source sentences (segments) into one in translated text or splitting longer sentences into shorter ones. This is actually quite easy: if you need to change long source sentence into two shorter in translation, simply write those two sentences into a single target segment. If you need to merge several short sentences into one, you can either join the segments so the software will show two or more sentences in a single source segment (translation table “cell”), or just translate fragments in proper segments. They will comprise a single sentence in output target file.

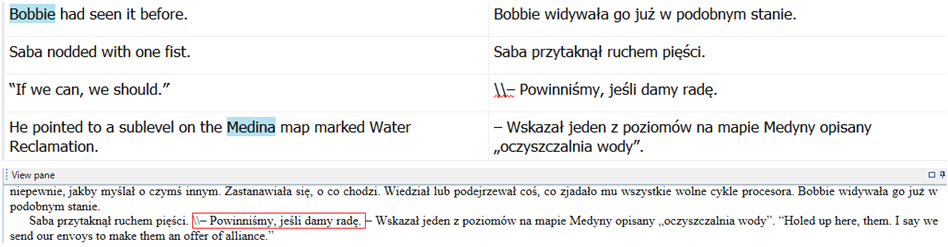

If you need to split text into separate paragraphs, you will have to use some placeholder symbol (I use “\\”) and use Find and Replace in Microsoft Word after exporting the translation.

And once you finish your translation, do the final proofreading of the exported target file in Microsoft Word, not in the CAT tool. This will help you see paragraphs and larger blocks of text, not sentences, in an overview which makes it easier to polish the text.

- Learning curve – You can grok the basics of CAT tool functionality with several hours of online webinars/training courses and a little practice, but you have to be prepared for some frustration and a steep learning curve, especially if you never used any such tool before and need to learn new concepts. Different programs offer different levels of complexity, and while general workflows are the same, implementations differ. When working with literary texts you won’t need all the features of a modern CAT tool, and some of the features mentioned above (such as web search) require some work for configuration.

- Cost – Let’s face it: CAT programs are professional software, and they are priced accordingly. Will your productivity improve enough to justify investment of several hundred euros? Maybe, with time. And maybe not. But you can start with free software, like Open Source OmegaT, free to use SmartCAT (read the EULA carefully) or Wordfast Anywhere, try subscription programs, e.g. Memsource or experiment with trial versions of commercial tools like memoQ (my favorite, with a 45-day trial period) or SDL Trados Studio. But remember the old adage: you get what you pay for. I don’t want to knock the free tools, but you do get more with commercial desktop software.

So, let’s summarize. Can CAT tools be used in literary/creative translations? Definitely. Will they help? Yes, in many ways. Enough to invest in commercial tools? You have to decide for yourself.

Full disclosure: I’m not employed by any software company and I don’t get comission on any sales, but as a certified trainer, I do run commercial memoQ trainings.